History

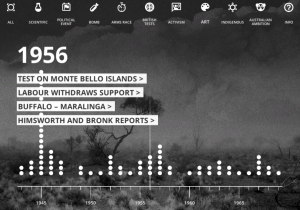

Interactive Timeline

We have developed an interactive timeline for the exhibition which gives you an overview of the most significant events of the nuclear history. It covers scientific discoveries, political events, protest movements, etc with a special focus on events in Australia.

We have developed an interactive timeline for the exhibition which gives you an overview of the most significant events of the nuclear history. It covers scientific discoveries, political events, protest movements, etc with a special focus on events in Australia.

Click the image to view the timeline – it will open in a new tab.

The timeline has been optimised for desktop browsers and tablets. It will not work on most smart phones, sorry for the inconvenience.

Credits: Production manager: Linda Dement; Timeline design: Nori Beppu; Creative development: Andrew Burrell; Data structure: Jonathan Delacour; additional research: Jessie Boylan

Historical Background

On 27 September 1956 the British military tested the first of seven atomic bombs in a remote part of the Great Victoria Desert in central South Australia. In two series codenamed Operation Buffalo and Operation Antler a total of seven devices with yields ranging from 1 to 25 kilotons TNT were detonated via plane drop, tower and ground level explosions.

Fireball from the British atom bomb test explosion at Emu Field (Operation Totem1), 15/10/53. Photo by News Ltd / Newspix

Prior to these, two atomic tests had been conducted at Emu around 200 km north of Maralinga in 1953 (Totem 1 and 2), although the British always knew that the site was unsuitable for long-term use and would only be temporary. Three devices had been detonated in the Monte Bello Islands off the coast of Western Australia near Onslow: one in 1952 (Operation Hurricane) and two more in 1956. The second Operation Mosaic test in 1956, codenamed G2, was the largest nuclear explosion in Australia with a yield of between 60 and 98 kilotons (the exact figure is disputed). Fall-out from the test was recorded as far away as Rockhampton on the Queensland coast.

The British government set out to develop atomic weapons in order to strengthen their position as a global and military power after WWII. With the rise of the Soviet Union and the communist expansion in Eastern Europe, the British were relying on cooperation with the United States in the scientific development and testing of nuclear weapons.

However, in 1946 with the passing of the McMahon Act, the US government excluded their former WWII ally from the program and any future British atomic tests in the Nevada desert. The Act placed nuclear weapons development of the former Manhattan Project, which had been a joint effort of American, Canadian and British scientists, in civilian hands. The Act enabled the Americans to secure a technological and strategic advantage in atomic bomb production.

Initially, the British considered potential sites for atomic tests in Canada and Scotland, and on islands in the Gulf of Carpentaria and in Bass Strait, but none of these were suitable. In 1950 British Prime Minister Clement Attlee enquired in a top-secret private message to Australian PM Robert Menzies about the possibility of conducting atomic tests at the Monte Bello Islands off the coast of Western Australia. Menzies was eager to please the British and accepted immediately. Neither his cabinet nor the Australian parliament were informed or consulte.

Emu and Maralinga atomic test areas in South Australia (map by Anna Wolf)

After an initial site survey Attlee sent a formal request for an atomic test at Monte Bello. Menzies delayed the decision until after the 1951 Federal election, and the re-election of the Liberal-Country Party coalition. The general public was not informed that atomic weapons would be tested until February 1952. The first atomic test was conducted on 3 October 1952. Britain had joined the ‘nuclear club’.

In December 1952 the new British PM Winston Churchill asked Menzies for ‘agreement in principle’ for further tests on the Australian mainland. Surveyor and road builder Len Beadell chose a site 1200 km northwest of Adelaide, which was subsequently named Emu Field. Details about the nature of the tests were not conveyed to the Australians. However, potential contamination with radioactivity as a result of atomic testing was flagged. Menzies appeared unconcerned and gave the British the ‘green light’. In October 1953 two atomic bombs were exploded at Emu Field (Totem I and II).

Due its remoteness and the lack of water, however, the site was deemed unsuitable. Again Beadell set out to find a new test site. At this stage the British were firmly committed to an ongoing atomic test program. Only days after the Totem trials the Australian government received a formal request to establish a permanent test site and asked for logistical support. The Australian government cabinet approved the request in August 1954.

Construction began immediately at a place 200 km south of Emu Field, 40 km north of Watson, a railhead on the transcontinental railway from Adelaide to Perth. The location was named Maralinga, from the now-extinct Aboriginal language, Garik, once spoken by people in the Northern Territory. The word means “thunder”. Maralinga would become synonymous with atomic testing in Australia.

These days the remaining infrastructure is an indication for the scale of the program the British envisioned at Maralinga. The 2.4 kilometre airstrip is still the largest in the Southern hemisphere. Maralinga village (of which only a handful of original buildings remain) housed thousands of personnel at the height of the program. The ‘forward area’ is marked by an extensive grid of bitumen roads stretching across an area of 300 square kilometres.

photo by JD Mittmann

Over the course of the program an estimated 35,000 Australian military and civilian personnel worked at Maralinga. However, the British denied access to test results and scientific information. In 1956 the Australian government established the Atomic Weapons Tests Safety Committee to monitor British activities, but the Committee remained effectively powerless and, according to the findings of the 1985 Royal Commission in the British Nuclear Tests in Australia, ‘complacent’.

The test program was run by British scientist Professor Sir William Penney. Penney had been part of the Manhattan Project and had witnessed the bombing of Nagasaki. The English physicist Professor (later Sir) Ernest Titterton served as chairman of the Atomic Weapons Tests Safety Committee, which was supposed to oversee safety aspects of the test program a Maralinga.

The ratification of the 1958 US-UK Defense Agreement prematurely concluded the British atomic tests in Australia and allowed the British to resume joint testing at US sites in Nevada. However, over 600 so-called ‘minor tests’ were conducted at Maralinga until 1963, when US, UK and the USSR signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) limiting atomic tests to underground. Concerns about atmospheric pollution as a result of hydrogen bomb tests by the US, Britain and the USSR led to the ratification of the PTBT.

photo by JD Mittmann

After the conclusion of the test program the British conducted two initial clean-ups (Operations Hercules and Brumby). Contaminated debris included 2 kilograms of highly toxic plutonium was deposited in dozens of shallow pits which were covered with concrete, while an estimated 20 kilograms of plutonium were spread over a vast area of land as a result of the Vixen trials. Plutonium has a half-life of 24,400 years. Consequently, this area has been become inhabitable for generations to come.

At the conclusion of Operation Brumby a top-secret report (the Pearce Report) was handed to the Australian government and in September 1968 both governments signed an agreement that relieved the British of any further responsibilities and future liabilities.

In July 1984 a Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia was formed by the Hawke Labor government, after it was confirmed in Parliament by Peter Walsh, based upon work being done in May 1984 at Maralinga and Emu by ARL scientists, that weapons-grade plutonium was indeed buried at Maralinga’s Taranaki test area. A series of media reports raised questions about the incidence of cancer and other health issues among service personnel and civilians who had been employed at Maralinga.

Tommy Queama and Jack Baker hold the Maralinga land grant documents, 18 December 1984. The deeds returned to its Traditional Owners. Photo by Milton Wordley/Newspix

However, the British remained secretive about the true nature of the tests program, in particular the ‘minor trials’, and did not produce sufficient documentation for the Royal Commission, which also held hearings in London. However, it was revealed that these tests included safety experiments in which nuclear materials were exposed to conventional ballistic weapons, fire and physical damage. The Vixen trials in particular included highly toxic elements such as beryllium and plutonium.

Justice James McClelland presented the Royal Commission’s final report in November 1985. It constituted a scathing indictment of the British and Australian governments, in particular in regard to the lack of transparency, secrecy, incompetence, the lack of health standards and disclosure of risks. Most prominently, it criticized the treatment of Aboriginal people.

A series of recommendations was made in relation to the decontamination and clean-up of the test site. Costs were to be borne by the British government. Further recommendations included the eligibility to compensation for service personnel, and compensation for Aboriginal people.

In 1986 the Australian government announced a payment of $500,000 to Aboriginal groups as compensation for the contamination of their lands. At the same time it undertook negotiations with the British government about issues of liability and the future decontamination of the sites. The British agreed to participate in the negotiations on the basis that this would not constitute an acceptance of responsibility or liability. (Later, the Maralinga Tjarutja people were paid $13.5 million by the Australian Government to settle claims concerning contamination and denial of access to test site land.) A $100m rehabilitation project at Maralinga, in particular at the former test site of Taranaki, began in 1996. The British government contributed significantly.

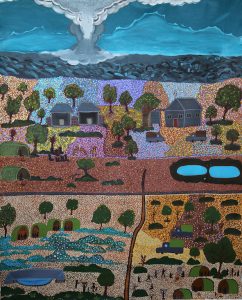

Cynthia Charra, Polly Charra,, Verna Gibson, Edwina, Ingomar, Glenda Ken, Teresa Peters, Carmel Windlass, Mellissa Windlass, Ann Marie Woods, Natasha Woods with assistance of Mima Smart, Margaret May and Rita Bryant (Pitjantjatjara Anangu) Maralinga Tjukurpa 2016, acrylic on canvas, 174 x 139 cm, Facilitated by Pam Diment, Courtesy of the artists © Yalata Community

The atomic test program had a significant impact on Aboriginal people and their country in South Australia. Pitjantjatjara Anangu people were removed from their traditional lands in the Great Victoria Desert and from Ooldea, where they had been living in the long-running United Aborigines Mission station until it voluntarily closed in 1952. Pitjantjatjara Anangu people living in the area where relocated to a new community, which had been established in limestone country at Yalata near Fowlers Bay.

The Royal Commission report condemned the lack of effort by the Australian authorities to locate free roaming families prior to the establishment of the Woomera rocket range and the atomic tests. The number of Aboriginal people who were present in the area during and after the tests and were subsequently exposed to radioactive fall-out and contaminated country is not known.

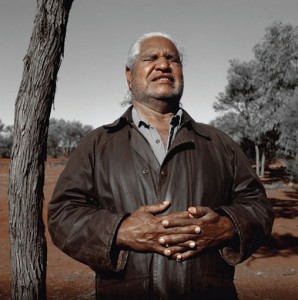

Jessie Boylan (Australia, b.1986) Yami Lester, Wallatinna Station, South Australia 2014, digital inkjet print, 85 x 85 cm, Courtesy of Yami Lester and the artist © the artist

Yankunytjatjara elder Yami Lester is probably the most prominent Aboriginal survivor and campaigner for justice. He became the ‘public face’ of the victims of atomic testing in Australia in the 1980s when he testified at the Royal Commission and visited London requesting that the UK Government take responsibility for the consequences of the tests. As he recalls in his autobiography, a mysterious ‘black mist’ hovered across the land approaching his family’s bush camp (after the Totem I test at Emu in 1953). He reported that many of his family fell sick immediately. He himself became blind soon after. White pastoralists in the area confirmed the existence of the ‘black mist’ that left a sticky black residue on fruit trees and windows. The trees soon after withered and died.

In 1984 the South Australian Government passed the Maralinga Tjarutja Land Rights Act, which legislated part of the Maralinga ‘forward area’ (Section 400) to be handed back to the Anangu as Freehold Title. However, mineral rights remained vested in the Crown and excluded veto rights of the traditional owners.

The remaining part of land, part of the Woomera Prohibited Area, was handed back by the Defence Department in 2014. Maralinga Tjarutja council now has full responsibility for entire area (3200 sq km). Regular surveying and ground water tests are conducted by the state and federal authorities, and will have to continue for generations to come.

For a more in-depth account of the British atomic tests in Australia see Elizabeth Tynan’s essay Thunder on the Plain in the exhibition catalogue. Her new book Atomic Thunder – The Maralinga Story has been published by NewSouth Books and can be found among other recommended literature in the resources section of the website.